Submitted by Vicky Yee K Reid on Mon, 17/02/2025 - 14:05

Dr Richard Milne, Head of Research and Dialogue at Wellcome Connecting Science, shares with us his thoughts on engineering biology and the importance of engaging the public in meaningful conversations, undertaking two-way dialogues and building trust in technology.

Engineering biology integrates engineering principles into biological systems and has potential applications across fields from health and agriculture to energy, and industrial production. However, as the recent House of Lords report on ‘seizing the opportunity of engineering biology’ emphasises:

Failure to understand and engage with the public could jeopardise some applications of engineering biology.”House of Lords: Seizing the opportunity of engineering biology

Public Awareness

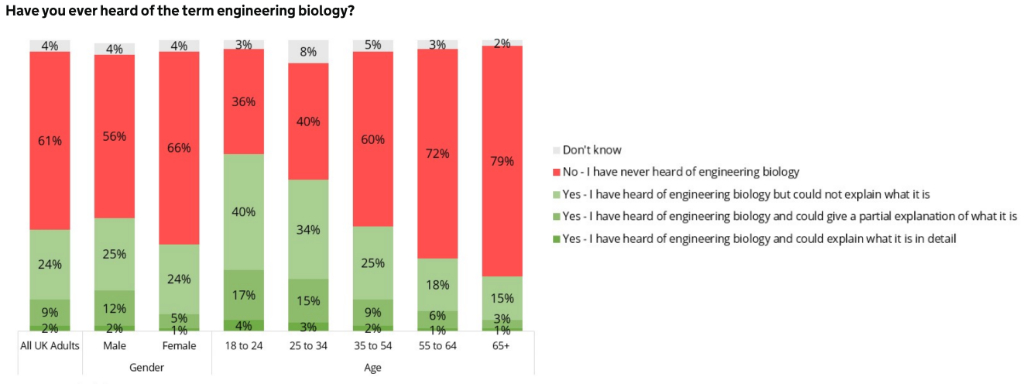

There is a dearth of recent literature on public attitudes towards engineering or synthetic biology. However, one core message from this literature is that public awareness of, and familiarity with, engineering biology remains low. According to a 2024 UK survey by the Department for Science, Innovation, and Technology (DSIT), only around 1 in 10 respondents felt informed enough about engineering biology to be able to give a partial explanation of it. Similar findings have been reported internationally. A 2021 Australian survey found that only 8% of respondents could describe synthetic biology to a friend, compared to 22% for GMOs. In the US in 2017, 75% of respondents reported feeling uninformed about synthetic biology.

61% of people have never heard of engineering biology

Learning from the Past

Views on engineering biology reflect not only views on the field itself, but on the domains in which they are applied and their social and historical context. Thus, the DSIT study suggests that respondents are comfortable with applications in health, energy, and sustainability, but less so for agricultural or food uses. The latter points to the legacy of GMOs that looms large over discussions of engineering biology. For more than a decade, "synbiophobia-phobia" —the fear that public rejection could hinder progress, prompted by the backlash against GM crops in the early 2000s — has shaped how policymakers approach engagement. While, at times, harking back to the GMO discussions may be unhelpful, it is potentially instructive in two ways.

The first way is that studies of public attitudes are rarely definitive or univocal. For example, the BSA review suggests a softening of attitudes in Europe towards GMOs - it highlights Eurobarometer studies that suggest that the level of concern about the use of GM ingredients dropped from 63% to 27% between 2005 and 2019. This is, however, in the near-total absence of cultivation. In contrast, the number of Americans who think GMOs are worse for their health increased between 2016 and 2019, and more than half of consumers across 28 countries say they reject GMOs, versus only 14% in favour. These responses suggest both genuine ambivalence and highlight the challenges of expecting people to hold pre-formed ideas about new technologies that are readily available to researchers.

The GMO experience is also, however, potentially valuable in what it can tell us about what matters in public engagement around novel applications of biology. Take, for example, the contrast between 'red' medical and 'green' agricultural applications suggested by the DSIT study. As a European study of public perceptions of agricultural biotechnology pointed out 20 years ago, this isn't simply about hopes for personal benefit from medicines. Instead, responses reflect values (in the case of engbio these may include religiosity (in the USA) and deference to scientific authority) and how people encounter and interact with red and green domains. This includes, for example, the extent to which they have open access to information, and how they feel about procedures for evaluating risk and regulatory processes. It helps explain why there is rarely a simple relationship between how much people know about science and how they feel about it.

The Importance of Trust

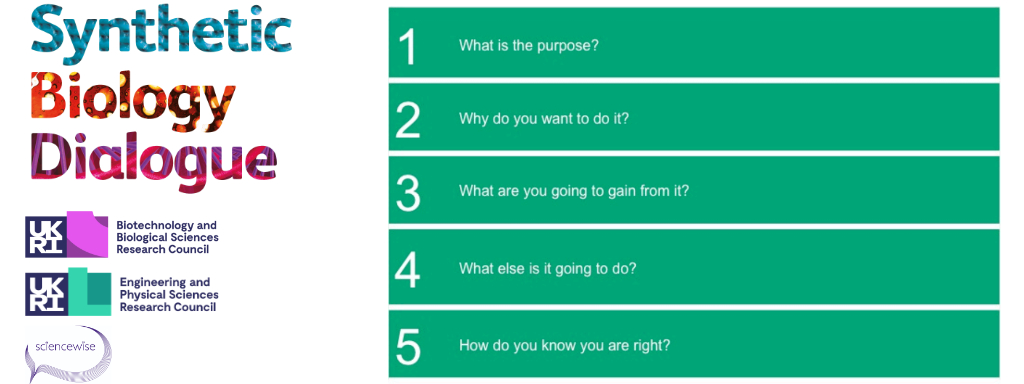

This leads on to the question of trust: public trust in scientists and scientific institutions, and in governments, industry, and the system that governs science; but also scientific trust in the public. Trust has been shown to play an important role in how people perceive the risks and benefits of new biotechnologies, and reflects worries about the motives of researchers and the consequences of commercial involvement, and the competence and integrity of both researchers and regulators. These concerns underpin questions such as raised in the 2009 BBSRC/EPSRC dialogue on synthetic biology, whose participants wanted to know:

- What is the purpose?

- Why do you want to do it?

- What are you going to gain from it?

- What else is it going to do?

- How do you know you are right?

A more recent dialogue conducted by the Royal Society similarly emphasised that participants wanted those developing new genetic technologies to be impartial and independent, expert and ethical, and to be working for science and the global good, not profit.

Key questions arising from the 2009 BBSRC/EPSRC public dialogue on synthetic biology

What next?

Dialogues bring together scientists and members of the public to exchange and discuss values, knowledge, aspirations and concerns. They provide a valuable forum for the creation of shared understandings and have effectively contributed across science policy areas over the last 20 years.

As we go forward with engineering biology, however, there is also a need to think about how we can build on this work - towards ongoing conversations between the public, researchers, and policy-makers, that builds trust and inputs into scientific thinking and decision making from the earliest stages. Building spaces for such conversations around discovery science has been one focus of the Hopes and Fears Lab project at the Kavli Centre for Ethics, Science, and the Public.

This month marks a significant opportunity to reflect on the evolving role of the public in engineering biology. Fifty years ago, scientists, alongside a few lawyers and journalists, convened in Asilomar, California, to deliberate on the risks and benefits of recombinant DNA tools—technologies that laid the groundwork for the contemporary field of engineering biology. Their agreement to pause certain uses of these tools until a framework for safe application could be established is often celebrated as a model of proactive scientific responsibility. Even then, prominent voices, such as David Baltimore, acknowledged the broader implications:

The issue was not an issue that scientists could decide ultimately for themselves in splendid isolation from the rest of the world.”David Baltimore

Half a century later, this sentiment remains highly relevant. Decisions about science and technology increasingly intersect with societal values, as members of the public are not merely recipients or users of innovation but active stakeholders. Effective engagement and involvement go beyond ensuring acceptance of final products — questions like, “Would you be comfortable with the use of engbio in…?” only scratch the surface. Instead, there is growing recognition of the need to foster collaboration between researchers, policymakers, industry, and citizens at the earliest stages of innovation. These conversations are crucial not only to shape the products of engineering biology but also to address the systems that create and govern them.

Dialogues can represent an important step toward these objectives, offering insights into how we might move forward. The challenge now lies in ensuring the conversations that dialogues enable are sustainable, mutually valued, and capable of addressing scientific and societal aspirations.

| Find out more about Richard's work, Wellcome Connecting Science and the Kavli Centre for Science, Ethics and the Public |